Are You My Mentor?

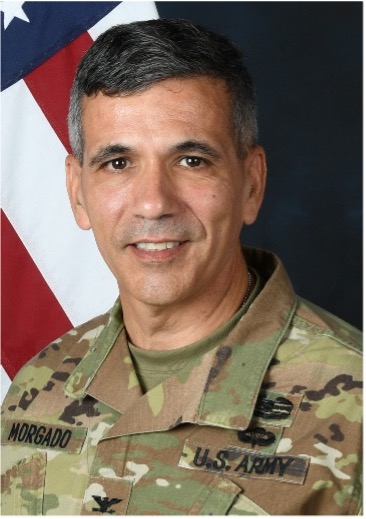

- Andrew Morgado

- Jan 12

- 6 min read

This article was also published in the Army Civilian Professional Journal (ACPJ) with authorized permission from Military Mentors as part of a cooperative publishing relationship. ACPJ may be found here: https://www.lineofdeparture.army.mil/Journals/Army-Civilian-Journal.

As a father and lifelong reader, one of my favorite activities was reading to my children. Not only did I wish to share my love of reading, but I often found the lessons in these books applicable to my adult problems. Among my favorite books was Are You My Mother? by P. D. Eastman. In this story, a young bird, hatched while his mother was away foraging for food, embarks on a quest to find her. In an eventful journey, this little bird encounters many possible, yet unfulfilling candidates—a kitten, a cow, a car, and even a steam shovel—until being deposited safely back into his nest by the helpful steam shovel operator. There, he joyously reunites with his real mother. In reflecting on my experiences as a mentor and a mentee, I realized that this bird’s journey was an allegory about the challenges encountered on the critical first step to mentorship—finding a mentor.

My own journey to find a mentor began much like our story’s protagonist. First, I did not know I needed a mentor. The persistent gaps and blind spots in my knowledge that I seemed unable to fill through my own self-study or discovery bothered me. Then after coming to the realization that mentors provide a means to fill those gaps, I did not have the first clue as to how to go about finding one. My initial instinct was to rely on former bosses. Though helpful, discussions were usually limited to my “next job” and general advice. There was never a deep connection or critical discussion about gaps or professional needs. The fault here lies with me, not my stand-in mentors. I did not take the time to take a good, hard look at myself and examine what I really needed to grow, learn, and develop. Most importantly, I did not advocate for myself and my needs. This is not about narcissism or arrogance; it is about taking charge of my own development. I let others take on that role and assumed my efforts would always speak for themselves. In the spirit of learning from the mistakes of others, I offer the hard-earned lessons of my struggles and propose “a way” to identify and connect with mentors much earlier in the developmental process.

In my time as both a mentor and recipient of mentorship, I learned that the single biggest stumbling block to effective mentoring is making the mentorship connection. This failure mostly comes from ignorance. We do not know what we need, who can help, and how to start the process. Perhaps the most damning misconception of all is a persistent myth that mentoring relationships “just happen” through some miraculous alignment of proximity, aptitude, and chance. Mentorship is not about chance. The most important thing to know about mentorship is that WE are responsible for finding and engaging our mentors. Mentors will not fall from the sky and make themselves available; we must go find them. This requires making ourselves vulnerable and revealing developmental needs for others to examine and, hopefully, help find a way to eliminate, reduce, or mitigate that part of our lives that may be holding us back. This is not easy. It takes moral courage. So, let us exhibit that courage and head out from the nest to go find our mentors.

Step 1. Recognizing Your Needs

We all have weaknesses or areas for growth. We also have blind spots. Though mentors will eventually help us with unrecognized needs, we need to start with what we know needs attention and fixing. Conducting an inventory with a well-known rubric may be a good place to start. As an Army professional, comparing proficiency in leadership attributes and competencies using the Army’s Leadership Requirements Model (ALRM) served as an initial self-assessment. A less formal guide may be a simple inventory of “what I do well,” “what I do not do well,” or “those things I wish I could do better.” Our reflection should make us uncomfortable and vulnerable; we must find ways to admit to our weaknesses. In the end, the tool does not matter; it is the act and process of honest reflection that does matter.

Step 2. Scan Your Environment

Finding a mentor becomes a much easier process when we know what help we need. This “what” helps focus our search for “who.” This may appear as an oversimplification, but we must start out with the basic question: “Who exhibits those attributes or traits we do not?” The answer to that question, in the form of another human being, immediately becomes a candidate-mentor. We need to find those people around us that exhibit the qualities we want to emulate. This becomes the basis for the next levels of inquiry. Do they share the same values? Do they offer a perspective that might be useful to us? Do they have the right experiences that will help inform our path? At this stage, we should not narrow our options; no one is “out of reach” or inaccessible. Never prematurely close off a possible venue because of rank, position, distance, or other perceived limitations. We need to keep our options open (at least until the end of step 3!).

Step 3. Reach Out Your Hand

Here is where moral courage must make its reappearance. Our candidate-mentors can never be an actual mentor unless we start the conversation. As the person seeking mentorship, we, the mentees, must begin the conversation. Remember, our mentors will not fall out of the sky. When initiating, we should not focus on cementing the relationship but rather frame the developmental need we are looking to address. Instead of asking, “Do you want to be my mentor?” ask instead, “I am trying to find a way to learn more about X. Can you help guide me?” If the candidate-mentor answers the first question, follow it up with another. The aim of the first and initial follow-on questions is to build rapport and, most importantly, trust. Trust is the sine qua non of a true mentoring relationship. Once we understand the need, establish a clear desire to communicate, and operate on trust, we have built a mentoring relationship.

Step 4. All Good Things Must Come to an End (Most of the Time)

Mentorship relationships are not “forever.” Frequently, they transition to something else, usually a friendship. Other times they go into abeyance and can be rejuvenated if a need resurfaces or a new one emerges. If the relationship fades, do not be concerned, as it is all part of the process. Sometimes this closure can be seen as a true mark of success; the mentor helped us where and when we needed it. A mark of a truly effective mentoring relationship is when mentor and mentee work cooperatively to build a network of mentors. A good mentor understands their limitations and finds other candidate-mentors to fill in gaps of knowledge. More mentors are always better than fewer mentors -- more perspectives allow for better informed decisions. We also sometimes outgrow our mentors. The perspectives offered by a particular mentor may no longer apply or, as the relationship matures, we realize that there are other people who may be a better match or have the right experience or perspective to address other developmental needs. As human beings, we know transitions are a part of life and, as such, they are also a part of the mentorship journey.

If we seek to grow as people and professionals, mentorship provides a ready-made tool to help us on that growth journey. It complements our own efforts of self-development and more formal learning and practice opportunities. The power of mentorship comes from this “informality” and its voluntary nature. Where counseling and coaching have more structure and requirements, mentorship’s power comes from its personal connection. Mentorship explores those areas frequently out of reach from more formal processes. We cannot be beneficiaries of all of mentorship’s benefits unless we exhibit the courage to be truthful about our developmental needs and reach out our hand to those ready, willing, and able to help. So, let us be honest with ourselves, seek out those around us that have walked the path ahead of us, and have the courage to reach out; we will not be disappointed. Unlike Eastman’s little bird, we can embark on our journey knowing what to look for and how to make the best of that opportunity.

References:

Eastman, P. D. Are You My Mother? New York: Random House, 2010.

Andy Morgado is a 30-year Army veteran currently serving as the military assistant to the Dean of Academics at the Command and General Staff College. Prior to assuming his current role, he served as the Director of Army University Press and was 18th Director of the School of Advanced Military Studies (SAMS). Over the last 2 years he has served in key leadership positions in support of the Army’s Command Assessment Program (CAP). He is a graduate of Lehigh University, Norwich University, and the Command and General Staff College.

Comments